Lucrèce Andreae on her Cannes selection and directing experience

Lucrèce Andreae on Grandpa Walrus, the Cannes Film Festival 2017 selection and her directing experience.

Geplaatst op 10 januari 2018

Lucrèce Andreae on Grandpa Walrus, the Cannes Film Festival 2017 selection and her directing experience.

Geplaatst op 10 januari 2018French director Lucrèce Andreae, after a warm reception and selection of her short animation Grandpa Walrus to Cannes Film Festival 2017 and other festival around the world, is already thinking of making a full-length feature film. Today she shares with CineSud Magazine about how it all began: her studies at animation film schools, developing of directing and animation skills and creating her short that led into great selections.

“Try to see your film as a step, not as an absolute aim.”

“Although the Cannes Film Festival 2017 Official selection didn’t change my life, still the best aspect of being chosen in such an important event in the film sphere is that it will help a lot to find some funds for new projects. When I say that my short film was in Official selection in Cannes, I see a little light in the eyes of my interlocutor. Everybody knows this festival and it’s a symbol of cinephile and quality, so yes, it helps to build my reputation! Moreover, I have got a great awards from the USA, another one from Canada, and also from Brazil.”

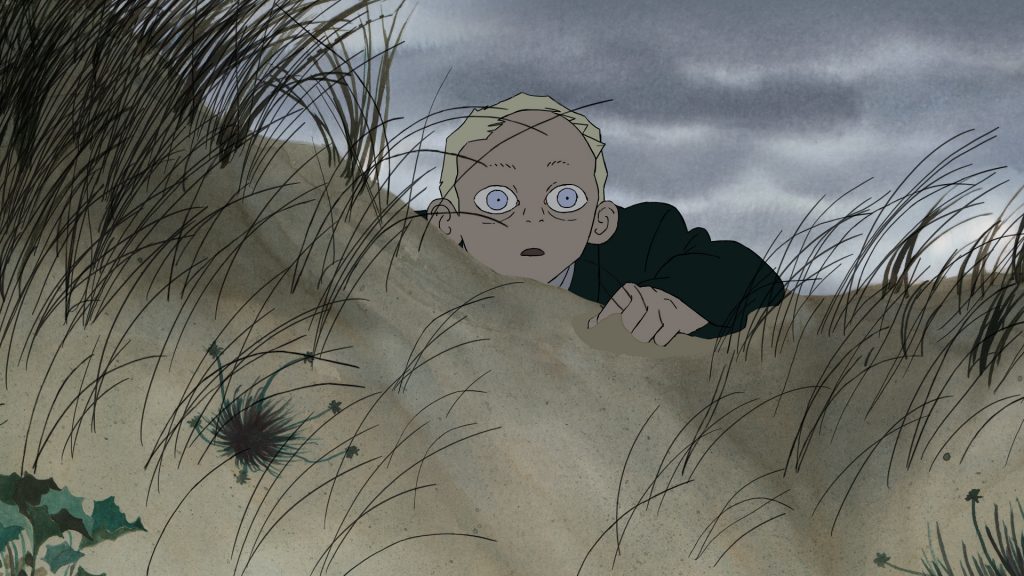

“Concerning the idea for Grandpa Walrus, I wanted to talk about death, the loss of a relative, and also about the complex links that exist in a family. I was inspired by the photographic works of Shoji Ueda: empty sand lands, lonely human beings, a touch of the absurd… All of this eventually found reflection in my film. I tried to create a cinematographic transcription of hard feelings and deep emotions about loss. The children’s point of view interests me the most because they don’t have all the keys to understand the adult matters, so they have to build their own interpretation that can be mystical, blurry, frightening. I also wanted to describe a ‘divided’ family with tough relationships, a realistic and quite vulgar language. It is a short film I decided to do as if it was a piece of a feature film. I wanted to try a rather classical way of writing and editing, a realistic rendering of atmosphere and space, credible characters and feelings, closer to ‘real’ cinema. Animation is often a tool to make more conceptual or visual experiments, or to describe an ‘archetypal’ world or a fantasy world, I wanted first of all to tell a story, that is what cinema brings to me everyday.”

“Even if technical questions were all challenges, it’s the emotional scenes that were the most tricky. The end of course, as always, isn’t it? It was difficult to find a good balance between comedy and drama. The theme, the death, is heavy enough: how to talk about it without being too melodramatic, how to keep some lightness, some hope without becoming cheesy… Besides the writing questions, it was very complicated to keep energy and motivation during four years… At the end I just hated my film, I couldn’t stand to watch it once more!”

“When I was a child I used to dream about becoming a children-books illustrator, and I kept this idea until entering the Estienne school, the illustration section, at 18, where I understood that I was not mature enough to find my own graphic style. I knew a friend who was studying at Gobelins, which is a famous French animation school, so I decided to follow his example and tried to enter it. My plan was: “I’ll study completely new techniques which will allow me to improve my technical level, and then I’ll be able to return back to my personal style”. At Gobelins I learned a large number of drawing, animation and storyboard skills.”

“After that I had the experience of studying in La Poudrière (French animation school specifically devoted to animated film-making), I focused more specifically on writing plots. I learned how to write scenario, serie concept, character’s identity, dialogues, and also to prepare a folder to present to channels or producers, to talk about a project, to find some funds, to run a team. La Poudrière is more a ‘director’s school’, while Gobelins is a technician school. In Gobelins the films are directed in groups (there were six of us to produce our graduation film, that’s why I can’t consider it totally mine), and there’s not enough of writing workshops. Therefore I entered the animation world almost by chance, however, I fell in love with the cinema and animation language at once. I am an artist as well, that’s the reason why I use animation and not real actors. I think both are inextricably matted, I can’t really distinguish them. Maybe my eye is used to evaluate picture, composition, colors, contrasts…”

“Talking about my directing background, I have produced five short films during my studies. Two of them are for children, as a part of a student competition organized by a TV channel in order to talk about the absurdity of the fashion in the playgrounds. My last graduation film, The Words of the Carp(from La Poudrière school), is about a speed dating and is laughing at some relationship’s scheme’s of people looking quickly for love.”

“I am thinking of making a full-length feature film, definitely! After the really warm reception of my short, I decided to write a script for a feature film for children, with my partner, Jérémie Moreau, who is a comic book author. I have recently received very good news that we had obtained a grant to write the script! I also began working on a comic book, I needed to find a way to tell a long story, alone, without the lengthy period of finance research, and quicker than in animation. Comic books are perfect for that, I’ll spend one year on them.”

“Try to see your film as a step, not as an absolute aim. Each film is a step to improve yourself, so accept that you will have a lot of faults, but you will learn a lot from each one! Another tip for first-time directors is basic: the complexity. My first research showed that it is better to avoid simplism, manicheism, to render the very deep complexity of the human nature and of the world, and to never judge.”