Chowra Makaremi - Documenting Evidence of the Iranian Terror

Sofia Piven in conversation with the documentary filmmaker Chowra Makaremi.

Geplaatst op 30 juni 2020The French director with Iranian roots, Chowra Makaremi, has been filming and editing her sincere documentary Hitch: An Iranian Story for 12 years. This film is about the unjust imprisonment and the execution of the person who is closest to Chowra: her mother. Because of this provocative movie the director is not allowed to visit her homeland now. Today she talks to CineSud Magazine about how she feels about the loss of her mother, how she started making films and about the reception of her film. She also tells the story of the Mojahedin-e khalq party, of whom her mother was a member.

"I have always wanted to know more but I thought everything was buried in the past."

The start of her filmmaking career

When Chowra Makaremi took a camera into her hands for the first time, she did not have the ambition of making a movie. Having studied words and theories during her PhD in anthropology, she was neither accustomed to working with images, nor had she any other experience in this field. Despite that, she bought a camera in 2007 and went to Iran, her homeland, to film places and people in order to find out more about her mother, a member of the Mojahedin-e khalq party; she was imprisoned and later executed due to the opposition to the Islamist authorities who were in power then. The director says: "Later on, when I thought of making a movie, I tried to remain faithful to this first impulse so as to produce Hitch: An Iranian Story with all my heart." Only in 2014 did Chowra start taking her amateur filming as a base for a documentary, trying to reveal some of the most terrible things in the Iranian history.

From the first impetus to an oeuvre

Why did Chowra suddenly feel the impulse to buy a camera to record a film in Iran that summer instead of just discovering more facts about her mother? Chowra cannot explain. However, she soon realised that the process of shooting is not only about bringing a camera: you have to take care of devices, keep the DVs safe and bring them back home, and primarily you must think of who, where and, especially in a country like Iran, how you film. Chowra explains: "You need an authorization from the Ministry of Culture in order to shoot in Iran but I did not have one. For this reason my research could not be spoken about loudly in public. Furthermore, my approach was rooted in something intimate, the family, so I had to consider the feelings of my relatives who sometimes were afraid to be shown in the film speaking about politics." For instance, there was no way to go even close to the prison where Chowra's mother served her sentence, although the director wanted to film that place, at least from the outside.

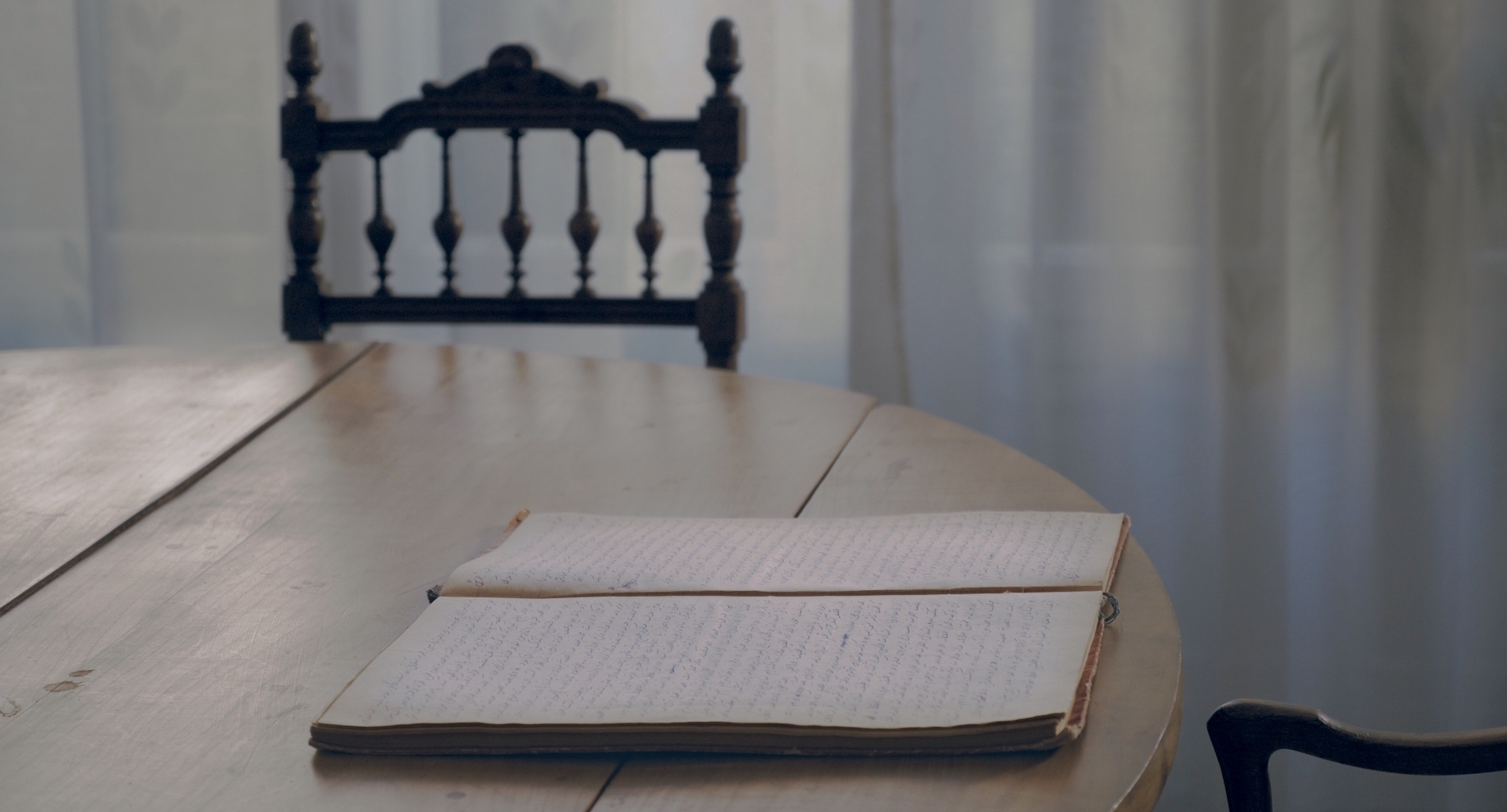

Chowra's developing desire to know more about these past political happenings, especially in connection with her own family history, were mostly triggered when she discovered a diary left behind by her grandfather. It is a hundred-page-long testimony, which was written a few months after Chowra's mother was killed in the 1988 massacre. She remembers: "My grandfather died two decades ago, but when I found his very powerful texts in 2004, it pushed me to do research devoted to my mom. I have always wanted to know more but I thought everything was buried in the past. I didn't see any thread I could follow that would lead me back to those events." Her grandfather's diary brought some hope: it was still possible to trace some facts and memories, even after all these years. It wasn't too late.

The life story of Chowra's mother

Chowra's mother was a high-school teacher in physics and a Mojahedin-e khalq party candidate in the town of Shiraz at the first legislative elections after the Iranian revolution of 1979. Her political career didn't last more than a year, since she was arrested right after the elections.

The Mojahedin-e khalq party was a political organization created in the mid-1960s. It belonged to the guerilla groups inspired by the anti-colonialist non-aligned movements. A specificity of the Mojahedin was that they promoted a political islam, merging together shiism and socialism, claiming that shiism was in essence a socialist religion. But their islamism was radically anti-clerical, contrary to the ideology promoted by Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Chowra says: "I know 'islamism' is a terrible word today, but the climate in 1979 was quite different. It was the beginning of the idea of political islam, things hadn't gone awfully wrong yet." In the time of the last Shah in Iran, the Mojahedin were persecuted by the SAVAK, the political police. After the revolution, the party firstly supported Khomeini but then opposed his project of an "Islamic Republic". Mojahedin-e khalq became one of the main opposition parties with hundreds of thousands of followers. They took part in the 1981 legislative elections, electing the first national assembly after the revolution; but right afterwards this the party was declared illegal and their followers were persecuted.

In the summer of the same year, the party leaders went underground and declared armed struggle, claiming several terrorist attacks. The hundreds of thousands of followers who supported the Mojahedin's program but were not involved in armed struggle, were imprisoned, tortured and killed. Most of them were teenagers or young people in their early twenties. Chowra's mother, Fatemeh Zarei, was among them.

Remembering her mother she says: "My mother was a Mojahedin-e Khalq's candidate for the 1981 legislative elections in the city of Shiraz. I think she was, first of all, an opponent to Khomeini's fundamentalist project. She was a revolutionary who did not want the revolution to turn into a totalitarian Islamic State. She believed in socialist islam, anti-imperialism and feminism. Her feminist involvement was quite strong, as she was the head of a women's grassroots associations linked to the Mojahedin. She definitely fought for the equal presence of men and women in the public and political spheres. She also organized extra-curricular, anti-colonial readings for her high school students. In her letters, she describes herself as an educator. I think she was a dedicated grassroots community leader."

Fatemeh Zarei was arrested for participating in a demonstration, where many were arrested and injured. She was then held in custody and "put on trial" because she was a Mojahedin activist. Being "put on trial" is put in quotation marks here because the trial before the revolutionary courts lasted five minutes, without any lawyers of course... Fatemeh Zarei was charged with "threat to the security of the State".

Activists, who were arrested after the Mojahedin's began armed struggle, were sentenced to death. But since Fatemeh Zarei was arrested before the party went into armed struggle, she was "only" sentenced to 15 years in prison. However, to everyone's surprise and horror, after spending a few years in jail she was executed.

Chowra comments: "The 1988 massacre was sudden and unforeseen. We still don't know why the authorities decided to kill all the remaining political prisoners at once over the course of a few months and in secret. The thousands of people who died at that time had not been sentenced to death when they were arrested. It was a brutal event that sealed this dark era of repression."

Chowra Makaremi was 6 years old when she moved to France. Since that time she had several opportunities to visit Iran. However, following the production of her film Hitch: An Iranian Story - she can no longer visit her homeland; it is too dangerous. She does miss the beautiful country, and more than the place, she misses the people who have resisted and continue to resist the brutality and inequity in their everyday lives.

The long path to the final version of Hitch: An Iranian Story

12 years passed between Chowra filming the first and the last scene of Hitch: An Iranian Story. But, all in all, it did not take more than a few weeks of pure shooting. Chowra remembers: "Editing was the longest part of the production, mostly because some strange accident happened in Iran, which put the whole project at risk, when we had almost finished it after 8 weeks of hard work."

The director collected testimonies and filmed interviews with witnesses concerning the graves of people executed in the 1980s, among which were Chowra's aunt and her husband. In 2017 these graves were destroyed overnight. It is still unclear who was responsible for such a cruel act, although, according to Chowra, it was probably endorsed by the authorities. She comments: "The reason why these destructions took place is that the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran is trying to erase traces and forensic evidence of the State crimes committed in the 1980s."

Consequently, people interviewed in the movie were afraid to talk publicly about an issue that was no longer an 'old story from the past' but had become highly sensitive again. The director finds it ironical: the movie's main theme is the denial of violence and State silence and now, because of this policy of denial, her team was compelled to cut out a lot of material from Hitch, including essential characters. Chowra remembers: "It was like unravelling and reshaping the storyline, reframing the story, redefining the esthetics… The challenge was that the life-span of my footage was shorter than the time it took to manufacture the movie."

An act of vandalism

Since a few years now, the demolition of political prisoners' graves is an ongoing process. Chowra tells CineSud Magazine: "Because some human rights reports have published evidence - mostly victims' testimonies of the mass torture and killings in the 1980s, the State wants to destroy further forensic evidence of these crimes." There is another motif discussed in the movie: desecrating the graves and whipping out the traces of those who have been unjustly killed as a way of terrorizing their families once again. It reactivates the fear. This is how trauma is used as a weapon of political engineering to maintain silence and create an artificial amnesia.

Chowra says: "I filed a claim concerning this case but received no real answer. The Department of City Planning in charge of building a road that is covering up the graves answered that 'we don’t know anything about this case, and we were not in charge'. However, the email address to which I sent the claim was hacked and deleted."

The bond between past and present

Hitch: An Iranian Story does not follow or reflect on Chowra's psychological journey. She comments: "The way I lived through the discovery of this past is one thing and what I unfolded in the film is another. In the movie it was rather the path of a person who could not accept the present, and only lived in the past. My 'hard work' of dealing with this past was done long before I started the film, and actually, that is what enabled me to work with the personal material. What I explored was how power 'scratches' our private lives, as Foucault put it. The personal is interesting because it shows how the intimate and the political are bound together".

Chowra has never stopped to live during the 12 years of work on this project or other related projects: she has a family life, she even gave birth during the editing phase of her movie. She admits that she does not feel the need to "run from the past". Chowra's perspective is not personal and psychological, but it is political and thus collective.

Her brother believes that the political fight belongs to their parents' generation during the Iranian revolution and they, as children, have to accept this past and live good lives. Chowra Makaremi does not see things like that, as if the only things left for the new generation were family happiness, individual success and a balanced private life. She says: "I simply cannot imagine my own life (and consequently my relationship with the past) in these terms. Of course, times are different, fights are different and I don't live in Iran, for instance. But still, my preoccupations are linked to showing repressions' effects on people's lives, even non-political people, and understanding mechanisms of violence to deter them in the future." Therefore, Chowra is not yet done exploring this topic. She is actually working on several other projects concerning the relevance of the past violence in Iran.

The director has found her inner balance while working on the film. However, it is not about balancing between the past, the present and the future, it is about finding a balance between artistic, ethical and political imperatives.

Her relatives' perception of the film

Hitch also became a controversial film for Chowra's relatives. Some of them, as can be seen in the movie, were quite fed-up with Chowra's stubborn interest in the past. Others did not feel comfortable with Chowra sharing their intimate experience of violence. Chowra says that violence and repression targets not only people, but also their private lives including family relations and affective bounds. This is how terror is produced. The director believes: "In order to show these mechanisms, we have to disclose the effects of violence. Intimacy is a battlefield for me, and being able to film it in the right tone and in the right framing is my way of fighting. But it is a personal battle. I totally understand that others do not share it. Some want privacy, some want security… My concern was also to respect these sensibilities."

This drew the boundaries for Chowra's film project: Do not create distress or rub salt in the wounds. However, there needs to be tension in a story. So, for the director this was a fine balance to find. She says: "I can say that in the end, the 'do no harm' rule prevailed, even over artistic choices, which can be frustrating... And there is a discrepancy with today's ideas regarding art, when for the sake of a movie, for the sake of cinema, art prevails over all other considerations." However, in the long run, Chowra's relatives did like Hitch, or at least found it sincere.

Internal satisfaction

Chowra is satisfied with the results of Hitch, mostly because the process of making it throughout the years was an extremely intense experience for her. She says: "If you had told me in 2007 that what I was filming was actually going to turn into a movie, I wouldn't have believed it. All the layers of filming and writing have developed my work." However, making Hitch did not go as planned and it met serious political challenges. According to Chowra, at some point, you either put others in danger or you have to renounce some parts of your project, which is what the director did. Nonetheless, it is a writer's job to find a way to get around such constraints. This is what makes art today, according to Chowra. The director says: "The encounter with violence and terror did not make my movie more powerful. I am afraid it made it less powerful. On the other hand, all of this gave me more knowledge about violence and it is useful for the future. It was worth the journey."

Disruption of plans due to the coronavirus

Despite the fact that, next to Hitch, Chowra Makaremi has only made one video essay called Antigone 88 (2009), which basically is sort of sketch of Hitch, she has already taken part in various different film festivals such as Etats généraux du film documentaire in Lussas, Les Ecrans Documentaires in Paris, the Jean Rouch Film Festival in Paris and Les Passagers du réel in Bordeaux. Other festivals, including the world premiere of Hitch, have unfortunately been cancelled due to the coronavirus.

Chowra is surprisingly fine with the fact that her plans to participate in various festivals were disrupted due to the imposed quarantine. She says: "I do miss wonderful opportunities to show my film in Linz, Istanbul, Paris, and Firenze, but there will be other places and times. My film is not about a hot topic, so it will not become out of date." Many people say that our concerns will change "in the world after corona" but the director is sure that questions of justice and impunity will remain relevant.

The coronavirus also influenced Chowra's plans for future projects. She had a shooting session for a new project this summer, which is postponed now. In the director's point of view, beyond logistics, this crisis will also influence how we make films and what we want to share.

For now, however, Chowra spends less time with film and more time with her son.

(c) All visual material is used with the filmmaker's permission.